My Seventeen Years in Prison

Editor’s Note: Hamadi Jebali became Tunisia’s Prime Minister after the ‘Jasmine Revolution’ in 2011. Hamadi Jebali has been called the Nelson Mandela of Tunisia. Too many years he was one of the leaders of the opposition to the dictators who held power in the country. He fled Tunisia after being threatened by President Habib Bourguiba. When Bourguiba was replaced by President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, Hamadi Jebali returned to edit a newspaper. But his anti-government articles led him being imprisoned for a total of seventeen years, ten of them in solitary confinement.

When Ben Ali was overthrown in the ‘Jasmine Revolution’, Jebali and his moderate Islamist Ennahda party were voted into power. He became Prime Minister. But his time in office was short. Unable to get his own party to agree to an independent technocratic government, he resigned in February of this year. Hamadi Jebali spoke to Matthew Bannister through a translator to ‘Outlook’ from the BBC World Service about a lifetime of political activism and his many years as a political prisoner. This interview first broadcast on Monday 16 September 2013. On behalf of CSCS this audio podcast of BBC has been written by Md. Habibur Rahman Habib for the readers.

***

Matthew Bannister: What first inspired him to get involved with politics?

Hamadi Jebali: The beginning was… I was really infused by my father. I was about eight years old; Tunisia had just achieved independence. Then there was the ruling party the RCD (Constitutional Democratic Rally which was led into two parts. One was led by Habib Bourguiba and the other one was led by Bin Yusuf.

Bourguiba tried to get rid of Bin Yusuf and my father was one of the followers of Bin Yusuf. So Bourguiba did launch a massive campaign against all Bin Yusuf’s followers and my father was one of them. That’s why he was put in jail and we all suffered accordingly.

Matthew Bannister: Do you remember visiting your father in prison?

Hamadi Jebali: I remember it very clearly. I was so young. I was about eight and I used to beg my mother to visit my father. And eventually she relented. So, I went to visit my father and I had the little bag which includes some food for prisoners. And I was allowed to go into the prison and the prison ward if you like and I saw my father in this very dark and lone some room.

He had another man with him in the same cell. The other man and my father were, I think, the first political prisoners in Tunisia post-independence. The other man was eventually executed by Bourguiba but my father miraculously survived because they could not find enough evidence to sentence him to death. So, I do remember that incident very clearly and had massive impact on the rest of my life.

Matthew Bannister: You went to France to study engineering but I believe there as a student you were very strongly involved in student politics that particularly affected Tunisia. Tell me about that time in your life.

Hamadi Jebali: Politics has always been in my blood, obviously by the influence of my father and history. So, when I went to France to study engineering and in the field of energy actually, I joined the Islamic Student Society and that how became active in political Islam. My visit to Europe and France in particular had massive impact on my life.

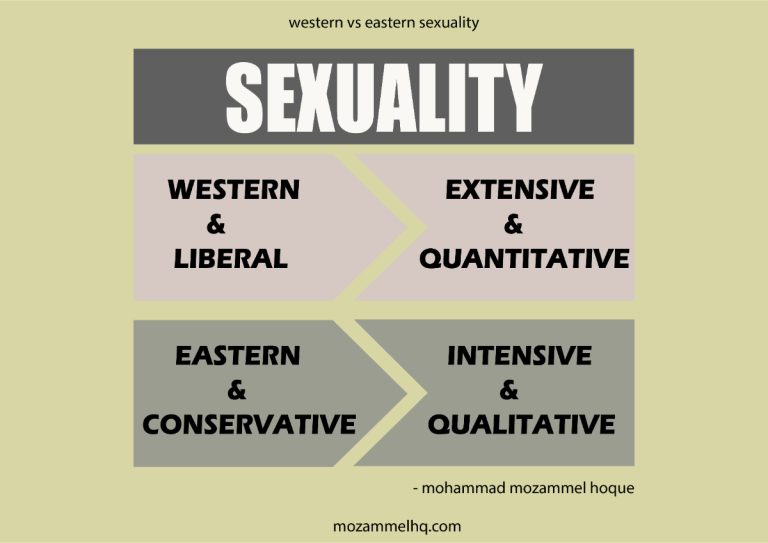

In France, I came to know proper Islam and its values. And this of course was tempted with democracy and freedom values. And I began to look into Islam and do all source of research and I could not see anything saying that there is a conflict between Islam, freedom and democracy. So, when I went back to Tunisia, I tried to introduce this mix in my life.

Matthew Bannister: When you returned to Tunisia, your political activities brought you into conflict with the government. I believe that there was even a threat to your life from President Bourguiba.

Hamadi Jebali: After Saleh Bin Yusuf was killed (executed) by Bourguiba, we thought Bourguiba would be a good ruler for Tunisia but he became dictator and he introduced the single party rule. He did not allow any other parties, whether leftist or Islamist or otherwise. And of course, he put us in jail and we suffered a lot because of that.

Matthew Bannister: You say you suffered a lot. What sort of deprivation where you subject to at that time?

Hamadi Jebali: Ben Ali became President after Bourguiba, who removed Bourguiba from power by a coup in 1987. Three years later in 1990, I was jailed under Ben Ali. I was jailed to sixteen years in prison plus one year for launching the newspaper ‘Al-Fajr’ as well. So that seventeen years in jail.

The difference between Ben Ali’s jail and Bourguiba’s jail is massive.

In Bourguiba’s prison we were political prisoner or prisoners of conscience. We were treated well. We were allowed a lot of freedom; we were not really tortured or treated badly. While under Ben Ali it was absolute torture, total disrespect and disregard for human rights.

I spend ten years of my seventeen years sentence in solitary confinement. He used to have us move to the far north of the far south of the country far away from our homes. So, our families when they came to visit, they had to go through hundreds and hundreds of kilometres. But they in the visit had only four, five to ten minutes maximum. We were not allowed books, we were not allowed to pray, and we were not allowed to have a Qur’an, copy of the Muslim Holy Book. In a sense, jail under Ben Ali was slow death!

Matthew Bannister: You used the word torture. Were you actually physically tortured while you were in prison?

Hamadi Jebali: No. I was not. I was never physically tortured but other activists and others who were member of this group were very severely tortured. However, mental torture is one I suffered all the time or this solitary confinement in a cell that was three by two metres, so tiny. I was only allowed out of this cell for fifteen minutes in a day. That was my break.

And When I was allowed that again I had to be of my own, I could not mix with anybody, anybody could not talk to anybody else, I was not allowed. So, mental torture is far worse than physical torture in my view.

Matthew Bannister: One of the hardest things must be that you were separated from your young daughters. But I believe you made presents for them from soap, and from olive stones. Tell me about that.

Hamadi Jebali: It was the hardest thing I suffered while in prison. I had three young daughters. Their mother had no income, so I left the three little daughters to their mother to look after them and bring them up. The police raided the house all the time and they were not allowing any visitors whether of my friends or family members to visit her freely. And of course, they would not let anyone give my wife money to help her.

And of course, I am eternally grateful to my wife. She put up with me while in jail, she put up with the police harassment and the mental torture and she looked after the girls who did very well at school and they graduated with honours. But this was one of my challenges, me personally I wanted to let my wife know that I care I appreciate her sacrifices and I also wanted to be involved in bringing up my daughters, rather than thinking I am in jail, so I am totally cut off from them. So, I used to use whatever was available to me. I used to be given one bar of soap a week. So, I used to use it to carve at models of animals and birds and also, I used olive stone to do same. And I carved worthy of thing that I gave them when they came to visit. I even carved the whole chess set for them which I gave them, they played with it. So, I am very grateful for my wife for all her sacrifices. I also love my girls deeply who graduated and did so well at school and in their education.

Matthew Bannister: So, when you were released from prison in 2006, it must to be in a very difficult thing to be reunited with your family. Happy of course but also difficult because you missed out on so much your daughter’s childhood and you had to get them all over again.

Hamadi Jebali: No, it was not that difficult because while in prison I tried so hard to find out what was going on around me and what was going on in the country itself. But my biggest shock and my first shock when I left prison, when I was released were to find that the surveillance that continued. So, there was no freedom really. There was still intimidating my family, they were intimidating my friends, at that time I actually thought over returning to prison because I could not cope with this kind of surveillance and this kind of torture and also my family being intimidated all the time.

Matthew Bannister: The ‘Jasmine Revolution’ began when a market stall holder called Mohammad Bouazizi set fire to himself. Did you recognize at that time that there was a moment that was going to an over-night change across Tunisia?

Hamadi Jebali: The Tunisian revolution did not begin with Bouzizi’s immolation; it began many many years before. Ben Ali came to power, who is a dictator and his dictatorship was combined with economic meltdown, with corruption every walk of life in Tunisia, there were loss of activist who were tortured, were jailed or were harassed. The Tunisian revolution culminated with Bouzizi’s immolation. He was the spark that set fire to the burn if you like. And I salute each and every one who took part in the Tunisian revolution and which culminated with the ‘Jasmine Revolution’.

Matthew Bannister: When you became Prime Minister, you said that you wanted to lead the government for all Tunisians. But your critics say that you are too tolerant of extremist Islamists. Is that a fair criticism?

Hamadi Jebali: No. Absolutely not! I was never too lenient on extremism. Somebody like me who wanted to promote freedom, democracy and social justice could not be ruthless to everybody. So, I told everyone in Tunisia whether on the right or the left his freedom respected and no weapons at all, because there is no dialogue with weapons. So, I was not too lenient with anyone. I made that very clear. So, when some of them did so, they were executed.

Matthew Bannister: Well, cause of the one of the high-profile incidents with the assassination of the opposition leader which added turning point for your government.

Hamadi Jebali: No. It was not that kind of turning point. It did not lead really to my resignation. The assassination of Chokri Belaid did not lead my resignation because I have thought it for a while. Simply because as a Prime Minister I was not able to do my job as I should have been. I did not want the transitional period to be long and that point in time it will be coming too long. I wanted the country to move forward to near normal life. So, I wanted to resign in the interest of the Tunisian People to form a government of a technocrat who can operate more freely and that’s what I did.

Matthew Bannister: It must be a bitter disagreement given the years you have spent fighting for Tunisia, given the time you spent in prison. That you could not continue as a Prime Minister that you had to step down. Which was a very sad day for you when you resigned?

Hamadi Jebali: No. I was not sad at all for one simple reason. I had never ever dreamt or wanted to rule Tunisia, to be the President, Prime Minister or even a Minister. I could have been a big businessman. Given my studies as an engineer, specialized in energy issues I could have had a massive project and became a businessman but I dedicated my life to the values of democracy and freedom. When it became clear to me that I was not being able to do just that as well, I decided to step down.

Matthew Bannister: Since the Arab Spring and the excitement of the Arab Spring there seems to be a sense of desolation and the sense that people who took power did not deliver on their promises. Are you optimistic about the future of Tunisia now or not? You step down. Are you pessimistic?

Hamadi Jebali: Of course, I am optimistic without that shade over doubt, I am very optimistic for Tunisia and I am also optimistic for democracy and freedom in Tunisia. The first value in Islam is freedom. So, I see the Arab Spring bring freedom to the Tunisian people, to the Arab people and the Muslim people across the world. I do not think any of them would continue before long under the thump of dictatorship and injustice. Therefore, I am very optimistic for Tunisia and for its future.